Rectal cancer

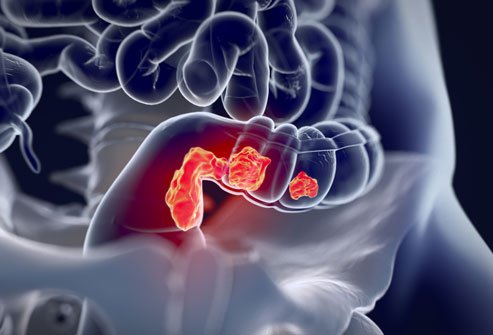

What is rectum or rectal cancer?

LThe rectum is the lower part of the colon that connects the large intestine to the anus. The main function of the rectum is to store formed stools for evacuation. Like the colon, the three layers of the rectal wall are:

LThe rectum is the lower part of the colon that connects the large intestine to the anus. The main function of the rectum is to store formed stools for evacuation. Like the colon, the three layers of the rectal wall are:

Mucosa: This layer of the rectal wall lines the inner surface. The mucous membrane is made up of glands that secrete mucus to facilitate the passage of stool.

Muscularis propria: This middle layer of the rectal wall is made up of muscles which help the rectum maintain its shape and contract in a coordinated way to expel stool.

Mesorectum: This fatty tissue surrounds the rectum.

In addition to these three layers, the surrounding lymph nodes (also called regional lymph nodes) are another important component of the rectum . Lymph nodes are part of the immune system and help monitor harmful materials (including viruses and bacteria) that can threaten the body. Lymph nodes surround all organs of the body, including the rectum.

Like colon cancer, the prognosis and treatment of rectal cancer depends on how deep the cancer has invaded the rectal wall and surrounding lymph nodes (its stage or extent). However, although the rectum is part of the colon, the location of the rectum in the pelvis poses additional challenges in treatment in relation to colon cancer.

Causes and risk factors of rectal cancer

Rectal cancer usually grows over several years, first developing as a precancerous growth called a polyp. Some polyps have the ability to turn into cancer and begin to grow and penetrate the wall of the rectum. The actual cause of rectal cancer is unclear. However, the risk factors for developing rectal cancer are:

Ascending age.

Smoking.

Family history of colon or rectal cancer.

High-fat diet and/or diet primarily of animal origin.

Personal or family history of polyps or colorectal cancer.

Inflammatory bowel disease.

Family history is a determining factor in the risk of rectal cancer. If a family history of colorectal cancer is present in a first-degree relative (a parent or a sibling), then colon and rectal endoscopy should begin 10 years before the parent's age of diagnosis or at 50 years, whichever comes first. . An often overlooked, but perhaps most important, risk factor is lack of rectal cancer screening. Routine screening for colon and rectal cancer is the best way to prevent rectal cancer. Genetics may play a role because Lynch syndrome, an inherited condition also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or HNPCC, increases the risk of many cancers, including rectal. Although human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are more linked to anal cancer and squamous cell cancers around the anus and anal canal, some studies show that they may also be linked to rectal cancer. Since some rectal cancers can be associated with HPV infections, it is possible that HPV vaccination may reduce the risk of getting some rectal cancers.

Symptoms and signs of rectal cancer

Rectal cancer can cause many symptoms and signs that require a person to see a doctor. However, rectal cancer can also be present without any symptoms, highlighting the importance of routine health screening. Symptoms and signs to be aware of are:

Bleeding (the most common symptom; present in about 80% of people with rectal cancer ).

Seeing blood mixed with stool is a sign that you seek immediate medical attention. Although many people bleed from hemorrhoids, a doctor should still be warned if rectal bleeding occurs.

Change in bowel habits (more or excessive amounts of gas, smaller stools, diarrhea ).

Prolonged rectal bleeding (perhaps in small amounts that are not visible in the stool) may lead to anemia, causing fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness, or rapid heartbeat.

A bowel obstruction.

A rectal mass can become so large that it prevents the normal passage of stool. This blockage can lead to a feeling of severe constipation or pain during bowel movements. Additionally, abdominal pain, discomfort, or cramping may occur due to the blockage.

Stool size may seem narrow so it can be passed around the rectal mass. Therefore, thin or narrow stools can be another sign of rectal cancer obstruction.

A person with rectal cancer may feel that stool cannot be passed completely after a bowel movement.

Weight loss: Cancer can lead to weight loss. Unexplained weight loss (in the absence of a diet or new exercise program) requires medical evaluation.

Note that sometimes hemorrhoids (swollen veins in the anal area) can mimic the pain, discomfort and bleeding seen with anal-rectal cancers. People with the above symptoms should undergo a medical examination of their anal-rectal area to ensure they have an accurate diagnosis.

What types of surgery treat rectal cancer?

Surgical removal of a tumor and/or removal of the rectum is the cornerstone of curative treatment for localized rectal cancer. In addition to rectal tumor removal, removal of fat and lymph nodes in the area of a rectal tumor is also necessary to minimize the risk of leaving cancer cells behind.

However, rectal surgery can be difficult because the rectum sits in the pelvis and is close to the anal sphincter (the muscle that controls the ability to hold stool in the rectum). With tumors invading more deeply and when the lymph nodes are involved, chemotherapy and radiation therapy are usually included in treatment to increase the chance that any microscopic cancer cells will be removed or killed.

Four types of surgeries are possible, depending on the location of the tumor in relation to the anus.

Transanal excision: If the tumor is small, located near the anus, and confined only to the mucosa (innermost layer), it may be possible to perform a transanal excision, where the tumor is removed through the anus. No lymph nodes are removed with this procedure. No incision is made in the skin.

Mesorectal Surgery: This surgical procedure involves the careful dissection of the tumor from the healthy tissue. Mesorectal surgery is performed mainly in Europe.

Low anterior resection: When the cancer is in the upper part of the rectum , a low anterior resection is performed. This surgery requires an abdominal incision and the lymph nodes are usually removed along with the segment of the rectum containing the tumor. The two remaining ends of the colon and rectum can be joined and normal bowel function can resume after surgery.

Abdomino-perineal resection: if the tumor is located near the anus (usually less than 5 cm), it may be necessary to perform an abdomino-perineal resection and removal of the anal sphincter. Lymph nodes are also removed (lymphadenectomy) during this procedure. With an abdomino-perineal resection, a colostomy is necessary. A colostomy is an opening of the colon in the front of the abdomen, where feces are eliminated in a bag.

Follow-up for rectal cancer

Since there is a risk of rectal cancer coming back after treatment, routine follow-up care is needed. Follow-up care usually consists of regular visits to the doctor's office for physical exams, blood tests, and imaging studies. In addition, a colonoscopy is recommended one year after a diagnosis of rectal cancer. If colonoscopy results are normal, the procedure can be repeated every three years.

Is it possible to prevent rectal cancer?

Proper colorectal screening leading to detection and removal of precancerous growths is the only way to prevent this disease. Screening tests for rectal cancer include a fecal occult blood test and endoscopy. If a family history of colorectal cancer is present in a first-degree relative (a parent or a sibling), then colon and rectal endoscopy should begin 10 years before the parent's age of diagnosis or at 50 years, whichever comes first. .